Dave Brubeck’s Jazz Impressions of Europe and Asia

Dave Brubeck’s Jazz Impressions of Eurasia

Musical Travelogues

During the Cold War, the United States government sent jazz musicians like Dave Brubeck and Louis Armstrong as cultural ambassadors to different countries, many of which did not maintain diplomatic relations with the USA. A part of their aim was to charm the Old World’s cultures with thoroughly modern music.

What in turn happened was that “foreign” influences were brought to jazz, which was, at that time in the Fifties, at the height of experimentation. Consider: Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come and The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s Jazz Impressions of Japan.

Brubeck wrote a travelogue of his tour from the States up to India, covering different countries. I have reproduced the intensely interesting travelogue from the original liner notes of the album Jazz Impressions of Eurasia and supplemented it with entries from his diaries and the interviews he gave over the years. Mind you, you won’t find these original liner notes anywhere today – not even on the modern reprints of the album.

So, read on and enjoy!

Jazz Impressions of Eurasia

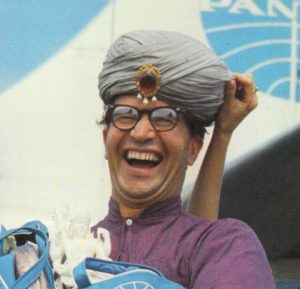

In early February 1958, the Quartet and I boarded a Pan American Clipper for London. Our tour, which began in England, took us through the countries of Northern Europe, behind the Iron Curtain into Poland through the Middle East (Turkey, Iran and Iraq) and on into India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Ceylon. When we returned to New York in the middle of May, we had traveled thousands of miles, had performed over eighty concerts in fourteen different countries, and had collected a traveler’s treasure of curios (see cover) and impressions (hear record) of Europe and Asia.

As in Jazz Impressions of the U.S.A, these sketches of Eurasia have been developed from random musical phrases I jotted down in my notebook as we chugged across the fields of Europe, or skimmed across the deserts of Asia, or walked in the winding alleyways of an ancient bazaar. I did not approach the writing of this album with the exactness of a musicologist. Instead, as the title indicates, I tried to create an impression of a particular locale by using some of the elements of their folk music within the jazz idiom.

The heart of any musical work, jazz or classical, is not the theme itself, but the treatment and development of that theme. And the heart and developmental section of these jazz pieces are the improvised choruses. Therefore, the challenge in composing these sketches was not in the selection of a theme characteristic of a locale, but in writing a piece with chord that would lead the improviser into an exploration of the musical idiom I was trying to capture. At the same time, the piece must fulfill the requirements of a good jazz tune – that is, the chord progressions must flow so naturally that the soloist is free to create. Many melodies, which could have been developed into compositions if out music were completely written, have been discarded, because in these jazz impressions of Eurasia the improvisations by the soloists are comparable to the developmental section of a composed work.

How does one go about writing such themes? One way is to listen to the voices of the people. The music of a people is often a reflection of their language. I experimented with the words “thank you” as spoken in several languages, since that was the one phrase that I used most as a performer and a traveler.

One of the most fascinating countries we visited on our State Department tour was Afghanistan. We were in Kabul, a city the dogs came into at night from the outlying districts, so you’re not very safe on the streets. The dogs come in packs and they’re out for whatever they can hunt or find. One night in Kabul I was awakened by the weirdest sound I ever heard. It actually made my hair stand on end. The muffled beat of drums and the eerie tones of a lone flute came closer and closer to my compound. I held my breath as the sound slowly faded away down the road. I was told the next morning that I had heard the music of one of the many nomadic tribes that drive their flocks through Kabul into the Hindu Kush mountains. The drums were slung across the camel’s back and were played by the nomadic musician as he balanced precariously on top of the camel’s pack[1], plodding away into the night. The nomads ride through, and they string drums on either side of their camel’s as a signal of their arrival and to scare off the dogs. I thought that this wandering musician and I had much in common – each of us traveling across our worlds playing our music as we went. When I wrote the piece Nomad I tried to capture the feeling of that lonely wanderer. The steady rhythm is like the even plodding gait of the camel, and the quicker beats are like the nomadic drums or the clapping of hands. The intricacies of Eastern rhythms are suggested in Nomad by superimposing three against the traditional jazz four.

The German phrase “danke schöen” is the basis for the Bach-like theme of Brandenburg Gate. The root progressions of this piece are similar to those of a Bach chorale, with some modern alterations of the chord structure. We used the device of imitation and simple counterpoint in the development of the thee – in a manner reminiscent of Bach. Brandenburg Gate is a title with many connotations for me. I think of Bach and the Brandenburg Concertos, and of my own personal experience passing through the gate. As you know, the U.S. government does not recognize East Germany, so one must enter that country at his own risk. The State Department thought the best way for us to go to Poland was through East Germany, but it was against the law for an American to go into East Germany and cross the borders of this country without a transit visa. In order to obtain such a transit visa it was necessary for me to enter East Germany. A German lady named Madame Gunderlock, a very ancient promoter everyone seemed to know, was one of the few people who could go into East Germany through Brandenburg Gate. This was before the Berlin Wall was built. So they asked me to get into the trunk of her (Madame Gunderlock’s) car.

I refused. Americans were going to jail for lesser things than that, and disappearing for six months to years. I said, ‘I’ll get in the back seat. If they question me I’ll tell them why I’m going, and I hope I can explain it.’ I was going to meet somebody from Poland who had papers that would get me through East Germany to Poland. So Madame Gunderlock drove me to what looked like a police station: a huge room, cement floors, wooden benches, and nobody in there. I sat there for hours, alone.

After a long time a man came in, walked over and sat next to me, but didn’t say a word. I thought, ‘What does this mean?’ Finally, he said, ‘Are you Mr. Koolu?’ I said, ‘No, my name is Brubeck.’ He said, ‘No, you Mr. Koolu.’ I said ‘No’ and he got out a Polish newspaper. There’s a picture of me, captioned ‘Mizter Koolu’ – Mr. Cool Jazz! Well, we had our papers. I had to return and get the band and two of my children and my wife on the west side back through the Brandenburg Gate, with no one to help us in a country where everything was hard to do anyway, and I couldn’t speak the language, and I remember almost getting on the wrong train track to the wrong place… but I had a title for my new piece[2].

“Choc Teshejjur Ederim” (pronounced “Choktahsa-keraderam”) says “thank you very much” in Turkey, and spoken rapidly becomes the rhythmic pattern of the theme, The Golden Horn. The title does not refer to Paul Desmond’s saxophone (unless you care to interpret it that way), but to that narrow inlet of the Bosporus called the Golden Horn that divides Istanbul. Turkey, both literally and figuratively, is the bridge between Europe and Asia and I tried to reflect that mixture by using a modal-like theme characteristic of the music of Turkey, along with Western harmony.

When we were told that the A.N.T.A-State Department portion of our tour would take us “behind the Iron Curtain,” we were somewhat apprehensive as to how jazz would be received in Poland. When we got to Poland we traveled in a bus where the floorboards were out and you saw the road down through your feet – that’s how beat up everything was, the country had been destroyed so thoroughly, terribly.

We soon discovered that no matter how the world may be divided politically or ideologically that cultural ties are bound in tradition and that traditionally Poland is a part of the West. There were no musical barriers with this jazz-conscious public. They greeted us with warmth and friendliness that was touching. In each city, groups of students or musicians would guide us to historic and cultural landmarks, such as the restored “Old Town” in Warsaw or the castle in Krakow. Our last day in Poland, students of Paznan took us to the Music Museum where we saw a collection of musical instruments from all over the world. Of special interest was a room dedicated to the memory of Chopin. A statue of Chopin that had been demolished in World War II had been lovingly reconstructed. The visible scars across the face gave the statue impressive power and significance – like the crack in our own Liberty Bell. I saw a cast of Chopin’s hands, his death mask, and had the thrill of touching the pianos upon which he had performed. With these impressions fresh in my mind, we performed that night, “Dziekuje” (pronounced something like “chenkuye”), a theme I had written based on the Polish phrase of “thank you.” I had written it on the train. There was no time to rehearse it because we went right from the train to the concert hall. I just hummed it to the guys, and wrote out the basic chord changes, but we never actually sat down and rehearsed it. The piece uses some typical Chopin devices for the piano – the arpeggiated chords in the left hand, and large strong leaps of melody, followed by a descending step-like motion in the right hand. I told the interpreter that I wanted to call it ‘Dziekuje’. We performed it after the interpreter told the audience what it was. When we finished, there was an absolute, interminable silence in the hall, which was one of the most frightening moments of my life. I thought I had insulted the audience by linking the memory of Chopin to jazz. And then, suddenly, cheers from everybody – the place exploded with applause and I realized with relief that the Polish audience had understood that this was meant as a tribute to their great musical tradition, and as an expression of gratitude. For some reason, it was like the concert had become a church or a tribute or something. I hadn’t planned it that way.

I saw most of England framed in the window of a band bus and we traveled from city to city. What struck me most about England was that it looked exactly as it was supposed to look. It was like visiting a distant relative whom the family had described so often and so well that you recognized him immediately. My first walk in London gave me something of the feeling of the English people. I walked through the Marble Arch into Hyde Park, which was crowded with Sunday strollers. There were orators exercising their traditional right of free speech, and hecklers exercising theirs. Little boys in knee pants were playing cricket, flying kites or wrestling in the grass. Little girls in proper frocks were skipping rope, playing games and rolling hoops across the lawn. The identifying sound over all this activity was the airy lightness of the children’s voices at play. I tried to capture these impressions of London in my piece Marble Arch, by using a folk-like melody with the smoothly flowing harmony one generally associates with proper English music, followed by a rakish music hall interpretation of the same progression associated with the not-so-proper English music. Finally, there is a jazz interpretation of the same progression, using three consecutive pedal points lasting four bars each.

Millions sleep in the street every night in Calcutta. There were three plagues going on in Calcutta, and the taxis were used for ambulances and hearses. You don’t forget those kinds of things. Nothing can change you more than seeing the misery of this world, and the great good we can do.

The Indian musical tradition is far different from ours. It emphasizes intricate rhythms and pure melody without harmony. We jazz musicians do have one element in common with the Indian musician – and that is improvisation. We were extremely fortunate in having the opportunity to “sit in” with some of India’s best musicians. Of notable success was our attempt “to jam” with Abdul Jaffer Kahn on sitar and various Indian tabla players. We all felt that given a few more days, we would either be playing Indian music, or they would be playing jazz. I tried to capture some of the sounds from these sessions in Calcutta Blues. I used Indian techniques were adaptable to the blues. Throughout the piece there is a drone bass, which simulates the role of the tamboura. The piano plays no chords so that there is a purposeful lack of harmony as in Indian music. The piano is used as a strict melodic instrument such as sitar or ramonium[3].

Our drummer lays aside his sticks and brushes and plays finger drums much as the Indian plays the tabla. The sound of the Indian flute and other melodic wind instruments is simulated by the alto saxophone. The theme of Calcutta Blues is certainly not an authentic Indian raga, but there are Indian influences in the limited number of notes used in the theme, and in the restricted number of notes used in the development of the theme. Although we made no attempt to stay strictly within the thematic notes in our improvised choruses, as the Indian stays within the restrictions of the raga, we had the limitations of the raga in mind during our solos. In this way, we tried to capture some of the feeling of the Indian improviser and his approach to music in Calcutta Blues.

It is evident that once the pieces for Jazz Impressions of Eurasia were composed, that the creation of this album was as much the work of Paul Desmond, Joe Morello and Joe Benjamin as it was mine. In these jazz impressions they have proved themselves to be not only great jazz musicians, but improvisers with unique imagination and adaptability.

– DAVE BRUBECK

Howard Mandel adds

Brubeck has had other adventures as well. He recounts the famous stories of recording an impromptu collaboration with Indian musicians while electric current fluctuated, resulting in tape distortion; of bejeweled, tropically treated pianos being hoisted by twenty bearers through the streets for his performance; of being shot at by shepherds while flying through the Khyber Pass; of being rich with useless zlotys upon leaving Poland; of leaving Baghdad hours before his hotel was attacked during a spasm of violence.

“The wonderful vitality we get from performing… I think that is what keeps us going,’ says Brubeck. “You get so much back from the audience. I’ve gone out there sick, and at the end of the concert come off feeling just great.”

Compiled, edited and annotated by Ritvik Chaturvedi.

[1] Did he mean ‘back,’ instead of ‘pack’?

[2] When Brubeck returned to West Berlin years later to play the first concert East Berliners were allowed to attend there and began Brandenburg Gate, the entire audience in the 10, 000 seats Sports Palace stood up.

[3] I am sure he meant ‘harmonium’.