Rendez-vous through Delhi’s past

Rendez-vous through Delhi’s past

Just one day before it was about to wind up, I managed to make it to an exhibition of photos of Delhi from mid-nineteenth century to the present.

There were, of course, themes that the organizer Ambedkar University (New Delhi) wanted to highlight and had grouped the black-and-white and sepia toned photographs under different captions. It was clear the that exhibition was divided into two broad camps: one documenting the people and another documenting the changing landscape, with the gallery switching between the two. But, even then, one could rearrange and regroup the photos in so many different ways according to different common threads. Apart from that, there was one recurring name that stood out: Narain Prasad, the person who had clicked all the pictures at the exhibition (except a few) from 1930s through the early 2000s until his demise in 2014.

The photos throw up completely different worlds: poetic, Urdu vocabularies that people were familiar with, contrary to the heavier and harder Punjabi tongue that Dilliwallas speak today; bygone modes of transport whose aftermath is still felt in the behavior of Delhiites as they travel by the metro – a behavior best suited to traveling by the bus; and lastly, names and landscapes that they considered a part of their life. The photographs, like most pictures from the past, are quite misleading as one tends to romanticize the past as a much simpler time, as there is no way of knowing the difficulties those people in the pictures faced that might have been solved by modern systems and technologies in place. There are also little means of knowing how smelly or noisy the past might have been like, unless one stretches her imagination to its limits.

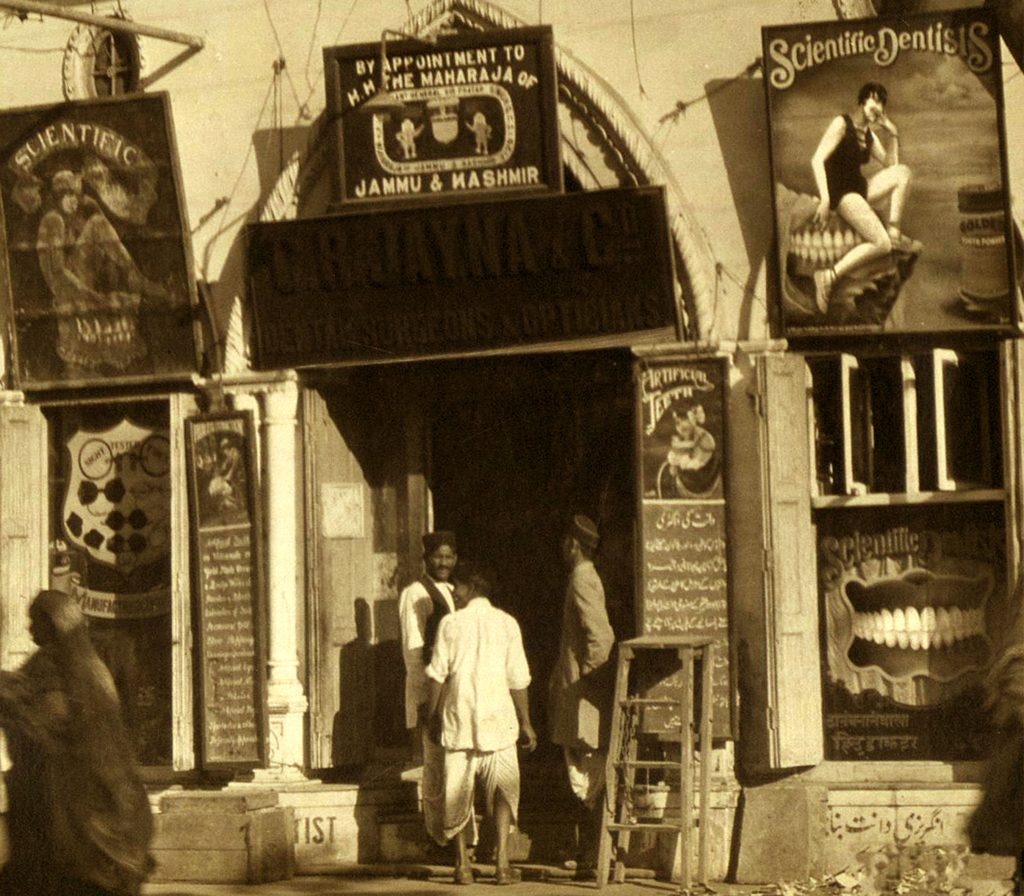

A case in point is the 1920/30s photograph of a dentist’s shop (Image 1) with fancy, flowing signs like movie posters of yesteryears. Those signs that read ‘Scientific Dentist’ were printed on paintings of skimpily clad women sitting on a set of teeth. Now, these were the days before anesthesia and dentists used laughing gas which, by the way, did nothing to mitigate the patient’s pain and merely translated his shrieks into laughs that prevented the dentist from aborting the operation. Despite most of us wanting to transport ourselves into that photograph, I doubt if anyone would want to actually avail the services of the dentist. Or, for instance, look at a 1970s’ color photo of Majestic Cinema, Chandni Chowk. The colors of the photo are warm, like most color photos from that decade. Now, I don’t know of anyone who would like to treat himself to the C-grade Hindi movie whose poster adorned the façade outside.

Image 1 Jayna Dental Clinic at Chandni Chowk, an early ‘scientific’ dental clinic, TIME-LIFE Archive, Year unknown.

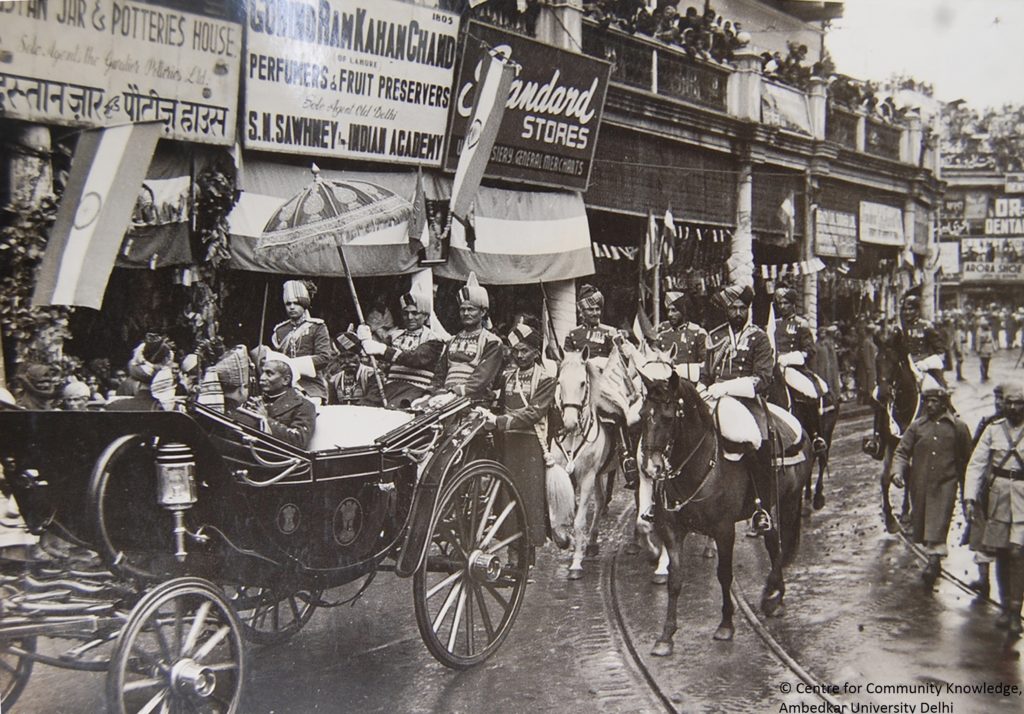

Politicians is a class without which one cannot imagine Delhi. There were ample photographs of them, in various positions, and I had come across some of the photographs before. All the pictures showed them at a higher head level than the meek people who sat around them. There was a picture of Karan Singh (still alive, President of ICCR), wearing sunglasses with a smug expression on his face. People sat on the floor around him (Image 2), some looking at him admiringly. There were a few ones of the Kennedy couple, then of India’s first President-Prime Minister duo. The most telling photograph was that of Rajendra Prasad’s cavalcade passing through Chandni Chowk (Image 3). The surrounding area is full of people with curious, bewildered expressions on their faces. Tram tracks, perhaps still in use, peek through people’s feet while the background is cluttered with signs of shops’ names that have suffixes like ‘Chand,’ ‘Lala,’ and so on. These photographs of Indian politicians were as good as those by Homai Vyarawalla and Kulwant Roy.

Image 2 Prof. Nurul Hasan and Dr. Karan Singh as part of audience at the Yaum-e-Ghalib, Ali Manzil, Fozan Ali Ahmed Collection, 1965.

Image 3 Dr. Rajendra Prasad in the presidential coach as the Parade passes through Chandni Chowk, Narain Prasad, 1950

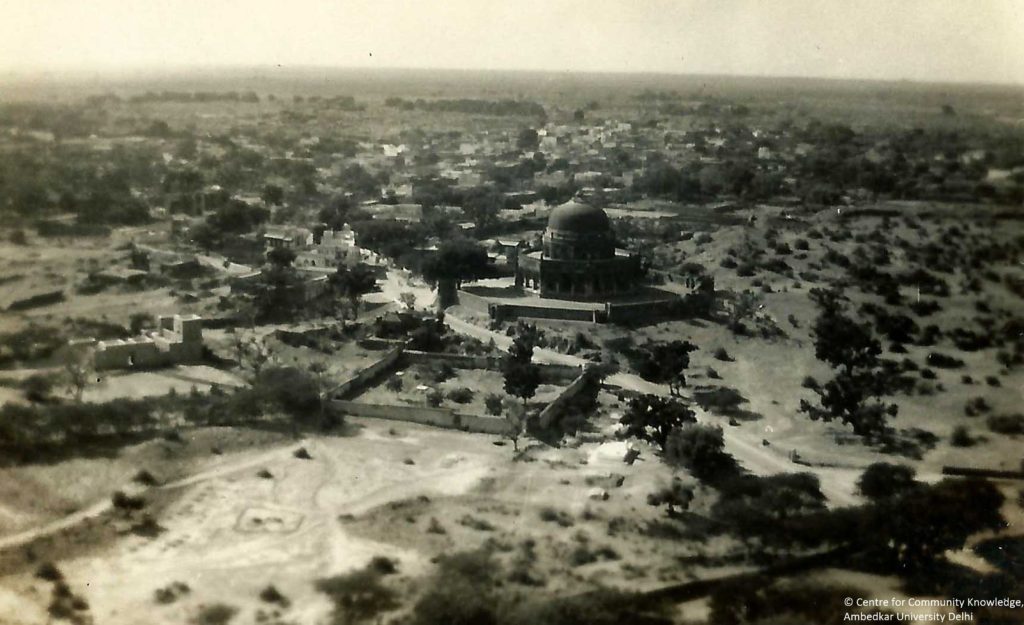

Vignettes from far South and Central Delhi present a different facet of Delhi. A soft-focus photograph clicked atop Qutb Minar shows Adham Khan’s tomb and the completely barren area around it (Image 4). I instantly recalled the fieldtrip I undertook with my seniors at National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore recently to document the area. Adham Khan’s tomb is now completely choked by shops and other modern structures. I guess Adham Khan’s tomb would have been visible from the bottom of the Minar when that picture was captured, and not just from the top. At least now it certainly is not.

Image 4 View from Qutb Minar, Mehrauli, Narain Prasad, early 1940’s.

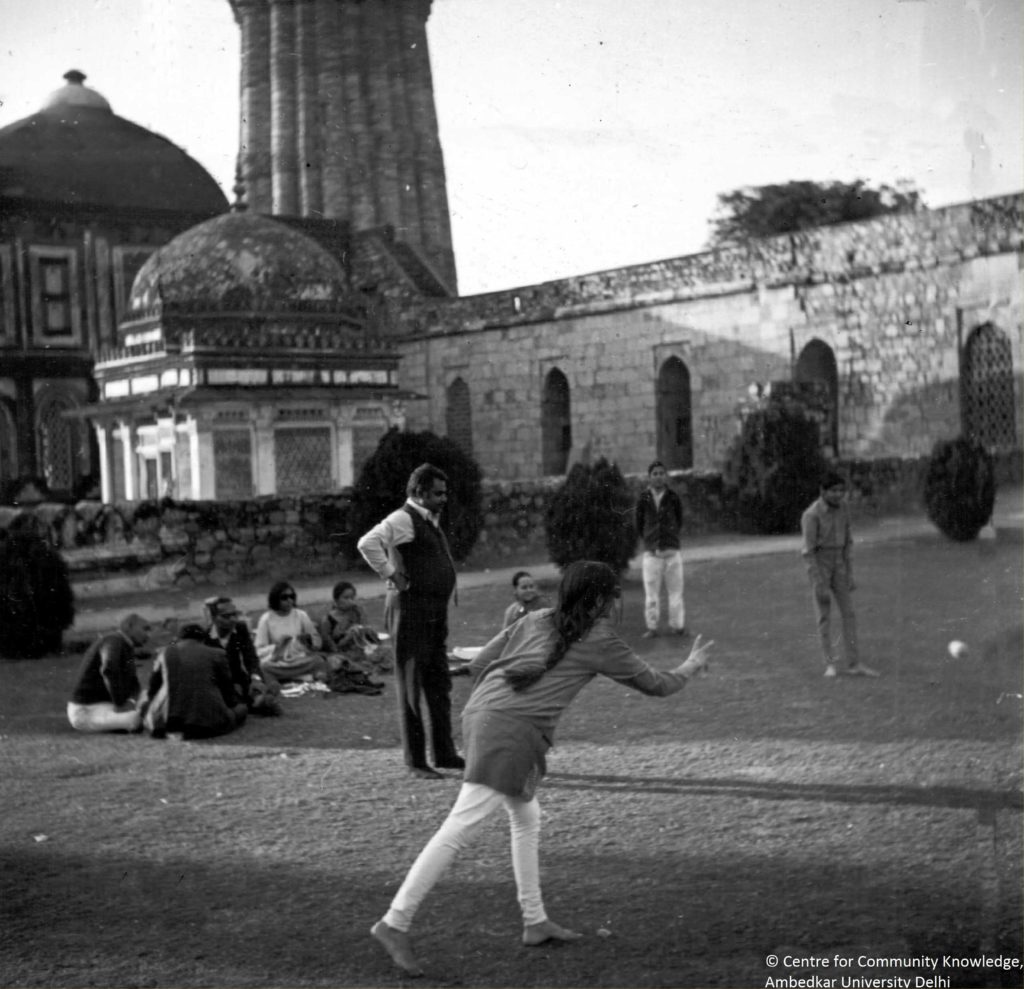

Other relics from the Delhi Sultanate – Tughlaqabad and Lodi Gardens – have their fair share in the exhibition. There is a family of visibly South Delhi élite in suits, boots and ties, wayfarers et al, playing cricket in the precincts of the Qutb Minar (Image 5). It was then that my friend quipped that ‘yeh woh log hain jinke bacche aaj Amrika mein hai’ (‘these are those people whose kids are settled in America now’). How times have changed. Nowadays, a person going to a park wearing formals would be considered an idiot or a show-off. But back then, it was noteworthy enough to be

Image 5 At Qutb Minar, Narain Prasad, Sunday, 26 December 1971. Hey, this is just one day after Christmas!

photographed, and acceptable enough to be photographed nonchalantly. Another 1931 sepia-toned photograph shows a wedding party in a vast garden with Anglo-Indian architecture in the background. The guests are not wearing any of the flashy clothes visitors to weddings wear today and are dressed in simple white saris and white suits (Image 6). Hardly any of them are smiling and are looking as morose as one can look into the camera, again unlike the selfies that come out of weddings today. The photograph has an extremely interesting caption (not by the organizers but one written in the original picture)that declares it as the wedding reception by one ‘Mr. Raghubir Singh, B.A.’ My friend and I were so envious of this man who lived at a time when one undergraduate degree was a qualification considered worthy enough to flaunt, unlike today when two of us – both Masters graduates – are essentially unemployed!

Image 6 Need I give a caption to this priceless picture?

Connaught Place, one of Asia’s most expensive markets and the go-to shopping destination for Delhiites from all economic classes is documented extensively in the exhibition. This is one place that is much better now than it was then. Today, it is well-connected by the metro; not very long ago, it took a car ride to get there although the roads were not as crowded as now. The photographs show near-empty roads, where the roundabout is free for pedestrians. One photograph from the late Fifties’, shot during Nikolai Bulganin’s India visit, shows a group of Indians assembled at what seems to be the Outer Circle, holding a banner declaring Russians and Indians as brothers, wherein ‘Russians’ was misspelt with a single ‘s’ (Image 7). I admit that with respect to the roads and the traffic, Connaught Place was better than it is today. But CP is appearing crowded per se. all the shop signboards, painted by hand, have been haphazardly put. There was no sense of proportion and all of them were scrambling to occupy every inch of space.

Image 7 Connaught Place looking festive during USSR Premier, Bulganin’s, visit, TIME-LIFE Archive, 1955.

If it hadn’t been for the Anglo-architecture of the place, anyone could have mistaken it for Chandni Chowk. In the 2000s, during the revamping of Connaught Place in the run up to the 2010 Commonwealth Games, a shop occupying a unit area of space was assigned only a fixed amount of display space for their signboards, and not an inch more. Nowadays, it is good to see all the signboards following a uniform standard for length and breadth and being in equal proportion to each other, that gives a semblance of orderliness to CP.

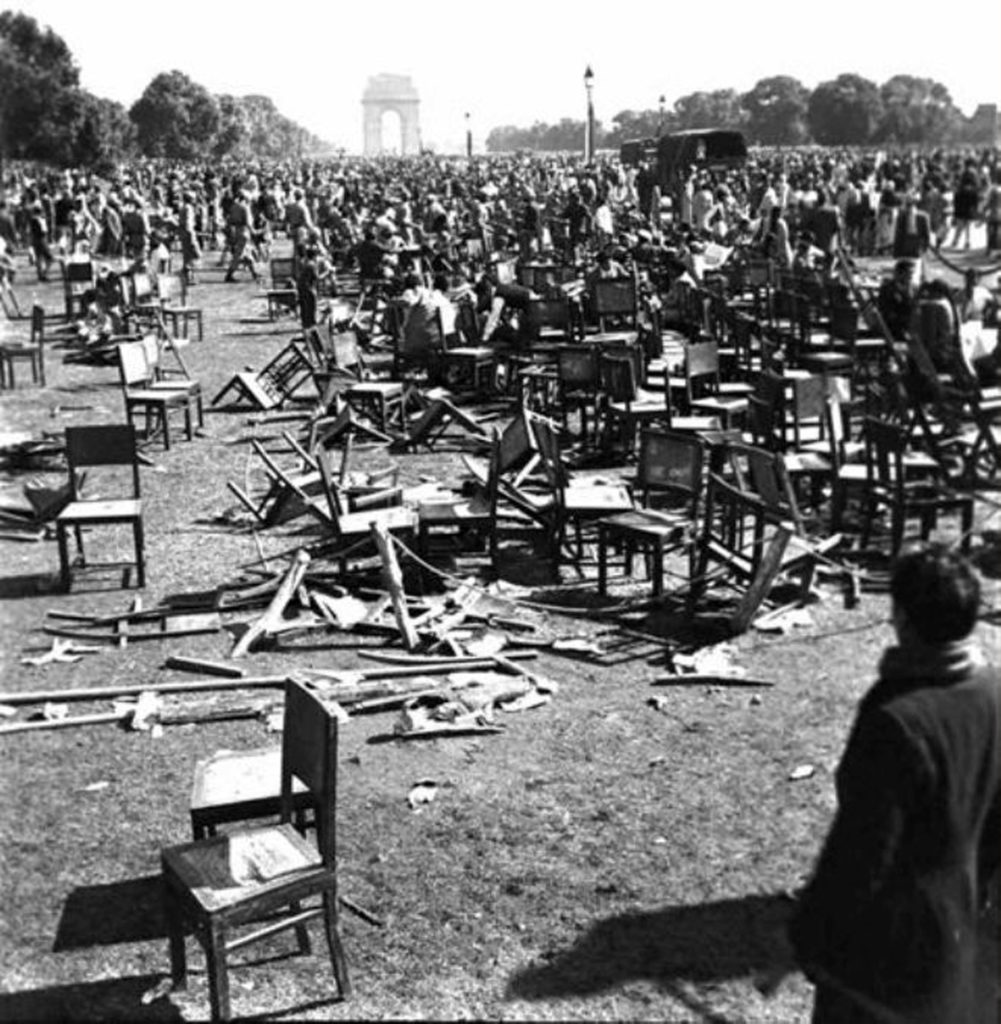

It is the commonfolk that lend a sense of life to a city. In the case of Delhi, they tend not only a sense of life but also decay. A scene from the aftermath of the Republic Day celebrations at Rajpath show dismantled wooden chairs possibly broken by visitors for the resale of wood (Image 8). A small reflection of the habit that cuts across the country. There are ample photographs of people carrying on their trades, spilling over public spaces. One single photograph of Chandni Chowk, which was crowded back then as it is now, shows at least four different trades. There is a watch repairperson in the foreground, a person selling pottery, cobbler in different corners of the picture. Another photograph shows a pavement completely occupied by a calendar seller, with a calendar showing Nehru rubbing shoulders with one showing a pretty woman on a beach (just like the man would have wanted in real life). The most appealing was a sun-bathed photo of a boy administering a shave on a man under a tree. The man getting his cheeks shaved gad his head rested on the chair, dozing off with the Sun beating on his face. Now, this was the photograph in which anyone would have wanted to participate. Finding such quiet corners in the city is not that easy now.

Image 8 Wrapping up after the Republic Day, Rajpath, Unknown, 1958. They literally wrapped the chairs.

The youth obviously formed an integral part of the people centric photographs of the exhibition. A 1960s picture of little children in proper school uniform receiving toys encased in boxes that had some Mandarin words printed on them from the Rotary Club (Image 9). The table has those typical, wooden triangular designation plates with words like ‘Secretary,’ ‘President’ and so on painted with white on them. Across the table, handing out toys, sit three men with big glasses and well-oiled hair. Those were the times when children had not yet started taking liberties with their school uniforms and men still thought that well-oiled hair was chic. Another photo shows slightly older college students in kurta-pajamas carrying flags with the sickle-and-hammer sign. Even today, they’re the only people who carry these Communist flags and are keeping the Left alive.

Image 9 Rotary Club of North Delhi presenting students of nursery class with toys, Narain Prasad, June 1972.

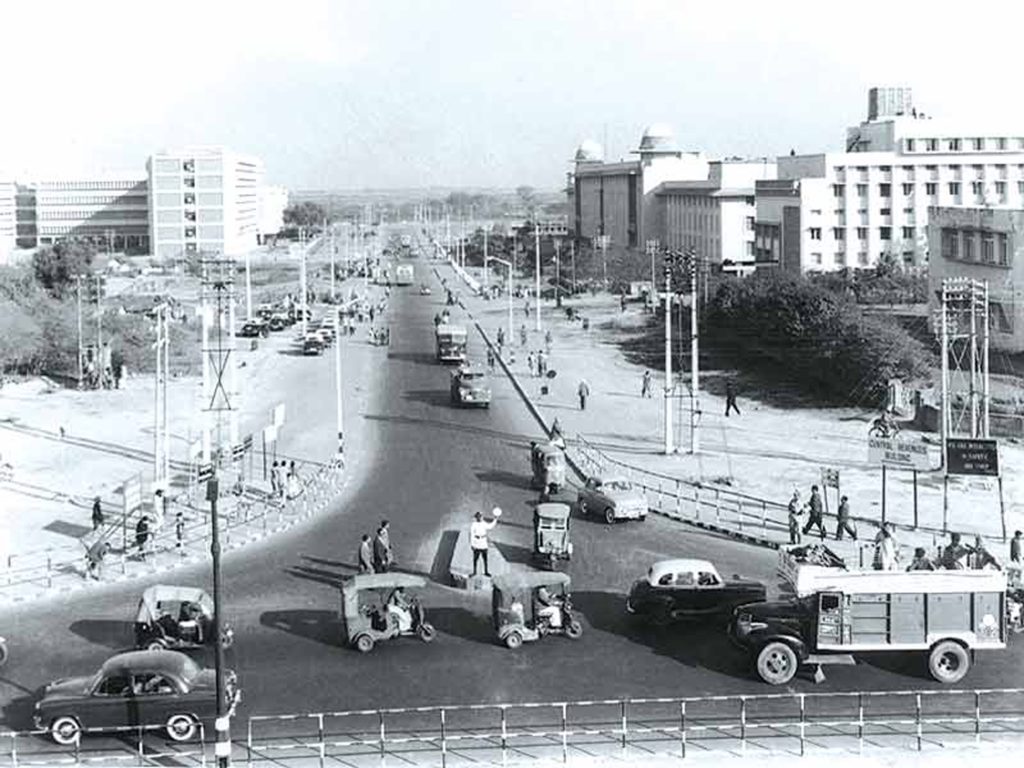

But people do not exist in a vacuum. They force changes in landscapes around them and that in turn forces changes in them. An old photo of ITO – the de facto boundary between the NDMC run and the MCD run area – shows a barren area except the building of Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, with its two domes. The Delhi Police Headquarters, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) Head Office skyscraper and the traffic are missing. The change in transport technology, visible in that photograph, stumps the viewer. In the old ITO picture, one can see an elongated auto rickshaw – a phatphatiya – that looks like a modern e-rickshaw (Image 10).

Image 10 ITO Junction Road, Unknown, 1950

Another 1946 photograph shows an airplane parked at the newly built Safdurjung Airport, with the Safdurjung Tomb in the background. Unlike the fancy, colorful airplanes of today, this one shows its steel skin, of just metal sheets nailed together. And none of those shuttle buses or extended passageways. If you had to board this one, you had to climb a rickety ladder like the one in the photo. One fan of the plane’s wing is still on whirring, on the verge of stopping. Maybe you can even make out the pilot peeking down from the cockpit. The men in the scene are all well-dressed in their best suits (Image 11). That was a time a time when flying was still a novelty for the ultra-élite and a momentous occasion even for them. Contrast that with today, when people book and take flights off-the-cuff, still in their night-suits.

The caption to this picture said: ‘Some forward thinking (my italics) Dilliwallas’ came to try this novel experience ‘and make acquaintance with the future of travel’. The caption is puzzling because I am compelled to think that people who came to try this were those who had the money to do so or lived close-by or were special enough to be invited for such a thing. People who lived close-by were certainly the élites of Lutyens’ Delhi and in 1946, a year before Independence, anyone who could afford a flight was certainly pretty rich. Though there is no ‘evidence’ or log of people who came to try this or even a list of the folks taking that international flight in the photograph, are they trying to say that people who did not come forward for this experiment were backward looking? I guess, in the near future, people preferring flights over teleportation will be considered backward looking. Lest I take it too far, let us not forget that there are still people today who detest flights for whatever reasons. In any case, ascertaining the advancement of thought (backward/forward) in people should not be contingent on the mode of transport they choose!

Image 11 Safdarjung Tomb visible in the distant background of an international flight at Safdarjung Airport, Margaret Bourke-White, TIME-LIFE Archive 1946.

While flying may have commercially taken off, no one can underestimate the import of road- and rail-ways in an ordinary man’s commute. There are plenty pictures of railway stations (even metro stations) and roads that Delhi residents recognize with and have done so for a long time. A 1939 photograph of the Loha Pul (or, the Iron Bridge) shows the bridge in construction, which was made initially for connecting Calcutta and Delhi. The old, yellow photo (Image 12) is juxtaposed with a 2016 photograph of the same, choked with cars (Image 13). One can even see two itinerant youngsters on their two-wheeler driving in the wrong lane, having fallen prey to the disease of breaking traffic rules that has severely afflicted our generation.

Image 12 Loha Pul at River Yamuna, Narain Prasad, c. 1939; and…

…Image 13 Traffic at Loha Pul, Ridhi Tirkey, 18 August 2016.

Looking at these photographs does throw up the changes our parents have seen and experienced. I wonder what a similar exhibition for our generation after a hundred years would it contain. Maybe a documentation of the change in Facebook layouts, because today’s Delhi is not worth being captured, framed and shown to future generations despite the advancements in photography?

Photographers credited wherever possible. Please see image captions for photograph credits.

All photographs courtesy Centre for Community Knowledge (CCK), Ambedkar University (AUD).

Do you have any old photographs of your city from your grand/parents’ albums? If yes, then please get in touch with me at mail@ritvikc.com.