The first week in UK

I was not jet-lagged, and the sleep I had got in fits and starts in the airplane had only made me repulsed with the prospect of slumber for the next few hours. My mouth was smelling foul, another reason I was in no mood to hit the bed. All I wanted was to clear my Immigration formalities and get a glass of water and mints as soon as possible. I later learnt that the box of mints I had carried from India was not empty, the mints had simply got frozen at the high altitude!

Yet, I stopped when I noticed photographs and panels of The Who, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, Pink Floyd on my way from the airplane to the Immigration Desks, capturing them at the Heathrow Airport as they returned from their first world tours. These were the people I had grown up listening to, so I absolutely had to stop to click a picture of those panels, even if it meant that people behind me would scoff.

The Immigration Officer happened to be in a good mood. This was not perhaps something new, as Rajiv Immanuel describes in his book Jewel to Crown, how the officer asked him, upon gathering he is an economics student, if he is a Keynesian or a Monetarist. When a frustrated Immanuel somehow uttered ‘Keynesian,’ the Officer roared ‘Damn all Monetarists!’ and let him through. My Immigration Officer asked me what kind of archaeology was I going to study there. When told, he bemused me by telling me he had worked on an archaeological site for two years, his hands all the while independently doing what they were supposed to do of their own accord. I could not understand the name of the site he told me, he had a heavy Northern accent. All I got was that it was a medieval Church.

I was most surprised when, after exiting the Heathrow airport, I came to a shop – the ‘authorized’ shop – dealing in things as apart as SIM cards and taxi bookings, and the lady manning the counter asked her colleague ‘pink charger dekha kya?’ (‘have you seen the pink charger?’). I then noticed that the lady was Indian, and she had tried best to dress herself up in a way to blend in the European working class. Had she not spoken in Hindi, I could not have guessed where she was from. Her colleague, it turned out, who understood Hindi was not Indian but Mauritian. In times when I see Indian youth shying away from speaking their mother tongues (this is especially in case of Hindi, in North India), it was pleasant to see my language being the lingua franca in London! My first encounter being in Hindi also helped me feel less away-from-home.

In fact, out of my first ten encounters in London upon arrival, few spoke proper English. The second person I met upon arrival was the taxi driver who ferried me to my hostel. He was Russian – I could tell that by the script he used on his phone’s GPS – and he too spoke little English. The lady at the hostel’s welcome desk spoke a thick Afro-American accent.

***

If you live in Delhi, listening to and seeing youngsters breaking traffic rules in a bid to move a few notches higher up the cool-o-meter is pretty common. You’d hear Punjabi songs blaring out of SUVs that have been parked anywhere on the road (saying that the driver just stopped driving where and when he pleased instead of ‘parking’ would be a more fitting description). You would hear and see Royal Enfields, with their silencers removed, racing on the roads and, more annoyingly, incessantly honking as if their ‘budbudbud’ sound was not enough.

So, when I exited London I was surprised to see a young upstart revving up his car engine in the parking lot. Well, at least the Brits have given up their pretences of being polite! I then realized a moment after that I should not have been surprised, as motor vehicles and the heroic imagery associated with them, thanks to advertisements, is actually a product of the West.

My trip from the airport to the hostel was uneventful, but with fair amount of surprises. There were similarities between the urbanscapes of Delhi and London. Large billboards for things from detergents to holidays abroad marred the landscape. They were strategically placed: within a five-kilometre radius of the airport, you are likely to see large billboards of telephone networks, targeting new visitors in seek of fortune, so that they might save money on international calls. The call rates were written in as large a font as the graphic designer would do with the low salary he got; meant to impress upon the mind of the tired tourist so she remembers which pack to purchase. You’ll see, in the same radius, large advertisements of holiday packages with photographs of beaches and mountains, meant not really for the tourist but for the Englishman returning home, so that he may start planning his next holiday immediately. Unbeknownst to the advertiser, the Englishman returning was most likely a tired businessman who had been sent by his company to a country which he did not want to visit as he knew he would return without seeing its choicest attractions. Next, you’re likely to see advertisements of cars and tyres. They would give a lot to chew on to both the new visitor and a seasoned resident: a newer standard of living to aspire to.

After a certain radius, advertisements of holidays are completely absent. Perhaps by now, the high of crossing continents is over and that lump of flesh sitting in the taxi had sobered down. By now, the chap has realized he does not have the money or time to go to another holiday anytime soon.

As if a testimony to the cleverness of advertisers, more homely advertisements take over as you move to Zone 4: bed mattresses, detergents, food and so on. For the casual onlooker, the dumb content of the advertisements deceptively hides the intelligence behind it. What is worth noticing is that they were selling the same products in India, and were able to present these products to the Indian audience, tying it seamlessly with Indian culture as dextrously as they presented it to the British audience, tying them with equal ease with British culture.

One week in London is sufficient to make it predictable. There are supermarkets everywhere. A Sainsbury’s, a Tesco, a Waitrose, an Argos, a Sainsbury’s, a Tesco, a Waitrose, an Argos, Sainsbury’s, a Tesco, a Waitrose, an Argos…

Nevertheless, the abundance of parks is really appealing.

***

The road to the hostel was remarkable in its silence. Living in India had got me accustomed to vehicular noise, honking and unnecessary revving up of engines. But throughout the way from airport to the hostel, I heard not a single horn. Being appealing to the ears was not the only thing, it was also appealing to the eyes in a way. There was a gap of at least one to two meters between two vehicles and no one overtook. The orderliness and obeying of traffic rules was impressive. Where I come from, you would be considered a rookie if you kept a decent gap between your car and the one in front of you. Most likely, a biker or another car would want to stuff itself in that gap or would, at least, honk and yell at you. Also, you would be expected to not drive in your lane and overtake haphazardly in order to show other people you are seasoned.

At the same time, there were places on the way that seemed so unusually out-of-place: for example, there was deep, black muck on the road and the kerb, with plastic waste floating in it, even as you could see trees extending their arms over wooden fences like a Constable painting.

***

Another thing that impressed me was that the driver refused to stop right in front of the hostel as it will obstruct the traffic, and instead chose to stop his car where the road designated him to do so. In India, it is the norm to stop your car exactly where your friend is waiting or wants to alight. You will easily find people rolling their cars in traffic and suddenly stopping for their parents waiting outside stores, so that their dear old mothers and fathers, unable to walk because of obesity (which is precisely why they became obese) would not strain themselves: a just repayment of all the effort they have put in in bringing up their kid. Not that we do not want to follow traffic rules, but it is just that the culture teaches us that the risk of coming across as rude to a friend is too high to bother following rules.

With a lot of luggage, I was unable to find my way. I had been forewarned never to ask for directions from passer-by’s in UK or EU, and only to ask from authorised information desks or policemen. But there were none to be seen. Online maps were not being of help, and I actually crossed my hostel twice before finding its entrance. It was on this occasion that a man walking by stepped up and asked ‘Ar’you lost?’ This was the first time I heard anything close to a British accent in Britain.

I have noticed that Brits do not greet people with a ‘How are you?’ Instead, they ask ‘You alright?’ (spoken as a slurred y’rrite?). ‘How are you?’ is closer to the Indian ‘kya haal hain?‘ while ‘You alright?’ is closer to ‘Aur, theek thaak?’ Considering that the Brits have their way of asking how you are, it might come as a surprise that the first word they speak in its response is ‘Hi,’ which in turn is an American inflexion.

***

The Post Office where I went to collect my one-year residence permit was in shambles and severely understaffed. Not ventilated (forget air conditioned), it was a furnace. Some of their payment portals were not working; and they did not seem to have computerized things yet and were working by hand. This had led to multiple, badly managed queues for the same thing. At one level, this was reassuring as I had earlier thought bad queue etiquette was something one would see only in India or Bangladesh. So, it was comforting to see the same in a developed country. Or was it because people in the queue were immigrants scrambling for their share of the cake? My experience in the metro aka Underground prove that it was not so, and that the Brits too shed their veneer of sophistication when things get going in a way they did not foresee. But more about that in the next section.

I did not expect this to be the case at the King’s Cross Post Office, arguably one of the busiest post offices and transport terminals in London. The place was littered with posters peeling off the walls taking with it the plaster that revealed the grey concrete behind. Remains of shops that were, large cheaply printed vinyl posters comprising largely of primary colours, with a thick yellow background, appeared to loudly proclaim ‘yes, we were here!’ Arial was essentially the only font used on those. They would appear gawky in the sleepy post office next to my Delhi home, let alone London.

***

Before I move on to academics in my next blog-post, I’d like to wind up whatever I have to say at the moment about London as a city. And no such description will be complete without a discussion of the Tube; and considering I come from Delhi, a city that has developed its own veritable metro infrastructure in the last decade, a comparison between London Tube and Delhi Metro is only expected.

Let me start by saying that the Metro is better than the Tube. Before your jaws drop on the floor, please allow me to explain why.

First of all, the Tube infrastructure is really outdated. One can perhaps excuse that as the Tube is the grand old man of transit networks in the world. But after a week of travelling in the Tube, I can relate to complaints of asphyxiation that the first passengers of the Tube expressed somewhere in the late nineteenth century. I think two hundred years and an Empire is enough to address that grudge.

The first time I entered the Tube was in the Piccadilly Line. I had problems purchasing the tickets. The ticket window so elaborately labelled ‘tickets,’ was blocked! I was later told that ticket distribution by a person at the counter was dispensed with in 2014. And I was not able to figure out how to use the machine, the options on them were not oriented the way I was used to on a machine of that sort at other places (like an airport). But I won’t blame the Tube for that as I was not used to it, and the sentinels at the station were most helpful.

When I entered Holloway Road station, it felt as if I was entering the intestine of a thermal power plant which flushes out its effluents. The moment you take the first step on the flight of stairs descending into the parallel landscape, you become familiar with a smell: a musty odour of rusted metal implements someone forgot in the attic, that are slowly evaporating away by strong wind and oppressive heat. Apart from being narrow, the walls were covered by an iron net that trapped crushed cola cans, cigarettes, newspapers, chocolate wrappers and other assorted evidences of urbanity. It was a vibrant archive for Tube history, except I could not open it, or even stop and photograph it without inviting the chagrin of people behind me. And yet, even today when I go through that staircase twice a day, I wonder how on Earth someone could squeeze through an entire can of coke or a box of cigarettes through the 2”x2” spaces in the net frame.

When I entered Holloway Road station, it felt as if I was entering the intestine of a thermal power plant which flushes out its effluents. The moment you take the first step on the flight of stairs descending into the parallel landscape, you become familiar with a smell: a musty odour of rusted metal implements someone forgot in the attic, that are slowly evaporating away by strong wind and oppressive heat. Apart from being narrow, the walls were covered by an iron net that trapped crushed cola cans, cigarettes, newspapers, chocolate wrappers and other assorted evidences of urbanity. It was a vibrant archive for Tube history, except I could not open it, or even stop and photograph it without inviting the chagrin of people behind me. And yet, even today when I go through that staircase twice a day, I wonder how on Earth someone could squeeze through an entire can of coke or a box of cigarettes through the 2”x2” spaces in the net frame.

In Delhi Metro, I had become used to huge, wide staircases that people did not use as they were supposed to. I thought that London will be better: the huge staircases will be replaced by ones even bigger, and the people will use those properly. So the narrow staircases were a shock.

In the Tube, I was instinctively looking for electronic charts above the doors, which show a map of the line you’re in, with each station a circle that shows red lights for stations passed and a green light for the station about to come. I have gotten so used to those in the Delhi Metro, and I feel they are really handy. One, the person standing does not have to crane his neck and see the marquee over the seats to know which station it is or is about to come. Two, it makes it amply clear the direction and the speed at which the train is moving. Three, it shows how many stops there are to your destination. You do not have to move your hands in that crowd to take out a relic of a Tube map from your bag – moving your eyeballs is enough. Despite this, I have not yet got used to the badly labelled signs in the Tube and turn my head to the space over the doors, as if it were a reflex action. I seriously feel that they could consider replacing advertisements of UK Tourism that show a clock that has since stopped working with a map, preferably an electronic instead of a static one.

The Tube trains are really narrow. No, you did not get me right. I said, ‘really narrow.’ What that means is that there is hardly one feet of space between line of seating of both sides. If you love London, I know what you are going to do: go to the train with a measuring tape, bump into some people, measure that distance and tell me it’s one-and-a-half feet and not one. If this train was running the Blue Line of the Delhi Metro, it would have burst to smithereens on the first day itself.

Another lacuna I found in London Tube was that they do not announce whether doors are going to open on the left or the right. Doing so would save so much confusion and avoid people trying to cross over to the other side. I saw this happening not only to tourists, but also to Londoners who were travelling in that Line for the first or after a long time. An easy way to do so is to have a map over the roof bracket that shows a stub jutting out at every station, with a stub upwards signifying right and a downward signifying left (or vice versa). Both these features, the audio announcement and the map, are there in the Delhi Metro and even the Bangalore Metro, so I do not know why it cannot be implemented in the Tube.

The biggest grudge I have with London Tube is that the floor of the Tube is higher than the platform floor. This makes it excruciatingly difficult for senior citizens, wheelchair bound people or differently abled people of any sort, and people carrying prams to alight. In the Delhi Metro, the station floor and the train floor are at the same level, and people might not notice it, but it makes it really easy for handicapped people etc. to board and alight. Not only that, it also prevents otherwise able-bodied people to fall or get their leg stuck in the gap.

Delhi Metro is infamous for people scrambling inside before allowing people to alight first. People in London are better. But during office hours, Londoners are only slightly better and will show their dark side if they are getting late for work. The announcer will cry hoarse, like in Delhi, asking people to refrain from pushing in – which some people obviously are oblivious to. The following is a photograph of the Tube:

Still, there is a fair amount of discipline as most people choose to wait for the next train, knowing the value of public order. Poorly labelled platforms not marking where the doors are going to open make people scattered all over the place, and thwart any attempt of queue formation. It is equally sad to think that in Delhi, even labelling those places on platforms where doors are going to open has not been able to make people stand in queues.

There is another thing that the Delhi Metro needs to learn from the Tube. In the Tube, at every landing of the stairs, panels on the left and on the right detail which platform one should take to go in a particular direction. While Delhi Metro has abundant signages in the platforms and in the trains, it will be helpful if they also have the same at beginning and landing of staircases.

Enough of rants, now some praise.

If the Tube leaves much to be wanted, then the Bus system of London is better than the Delhi one. The bus stops and maps designed for London are really intelligent. In Delhi, although it is easy to figure out which bus to take, it is difficult to know which side of the road you have to be on (as every bus stop with a name has two – one on each side of the road). That makes it necessary in India to ask people around who are familiar with the route. No such trouble is required while using a bus in London. First of all, the bus stop on each side of the road, both bearing the same name, have distinct alphabets which you can see from afar. For example, even if two bus stops are labelled Tavistock Square, with the help of alphabets one can understand which side will take him to Trafalgar Square and which side will take him to King’s Cross.

One does not need online maps to figure out, because every bus stop has three panels – two small and one large. One small panel details the bus routes and numbers, each with their own colour coding, all clustered with their respective ends on the top and bottom of the panels. It is not necessary that the Northern end will be denoted at the top of the panel, as is the geographical convention. The path that a bus has already covered is shown as ‘hollow’ i.e. white with only an outline of the colour code assigned to that particular bus number. The second small panel corresponds the first and shows the buses that run at night. Such buses are prefixed by ‘N’ and have an owl graphic drawn on them. In Delhi, while using buses, I had become accustomed to seeing all the destinations just dumped unsystematically, separated by commas, on one green board.

The large panel is an example of genius design. It has deliberately been made geographically inaccurate to facilitate ease of understanding. The bus routes, with all stops in between, are well-labelled, with alphabets symbolising the side of the road it will be on. The area of about one kilometre around the bus stop you are standing at is coloured in grey. The coloured area is in turn is enlarged in another map to the left of the main one, again detailed the bus stops with alphabets. I feel that had they had coloured the roads even in the enlarged map according to the bus routes, it would have been even better.

Within the same large panel, to be studied independently (or in tandem with the maps, depending on the viewer), detail each bus route going through that stop, plus bus routes going through every stop in 1 km proximity to that stop, with numbers and alphabets showing the road and the side. If that was not enough, there is another alphabetical list of destinations that show which bus route goes there, along with alphabets denoting the side of the road. I have not seen such a self-explanatory map lately!

***

There is plenty of garbage in the open in India. But after spending a week in London, it seems that the West too produces a formidable amount of plastic waste! I wonder why garbage in India makes to news and discussions, but the one in Paris or New York does not.

The open garbage in India, certainly more in density and number than London because of population, and certainly more harmful because of bad sanitation network which allows plastic to choke drains, is often attributed to irresponsible public. In London, I saw irresponsibility in a unique way. People try to shove their coffee mugs and used carboard cases their food in dustbins even if they were full to the brim, even if it means that the stuff previously inside comes out in the process of stuffing their waste in. I later realized it was because there is penalty of £80 for throwing garbage anywhere. Englishmen have come up with a noble solution: ensure your stuff goes in the dustbin, and throw thy neighbours’ stuff out if need be.

This is not an uncommon sight in UK:

***

Waterstones, a bookstore near UCL has a small section of vinyl records, an oasis, if I may say so, in a large section of popular history books of which I have had a fair share in the last five years. I had a record player back home in Delhi, here I do not and nor do I have the space for it. Vinyl records are anyway quite expensive. Many of these vinyl records here are of those albums that I used to own as CDs in Delhi (and thankfully still do!). But it is always a delight to see them in their full glory. The added bonus is that the records kept in Waterstones are sample pieces that I can open, absorb the artwork, read the liner notes and put it back as it was.

The section contains classic gems, mostly of music Britain is (and should be) proud of: Yes, King Crimson, Genesis, The Rolling Stones, Queen etc. I also noticed some forgotten Sixties’ masterpieces like The 13th Floor Elevators. Among more thoughtful and tasteful covers of The Doors and Jethro Tull, you find some jarring sleeves from the Eighties as well, with a strong techno and computer graphic influence, with Black Sabbath’s sleeves sort of forming the bridge between the two decades.

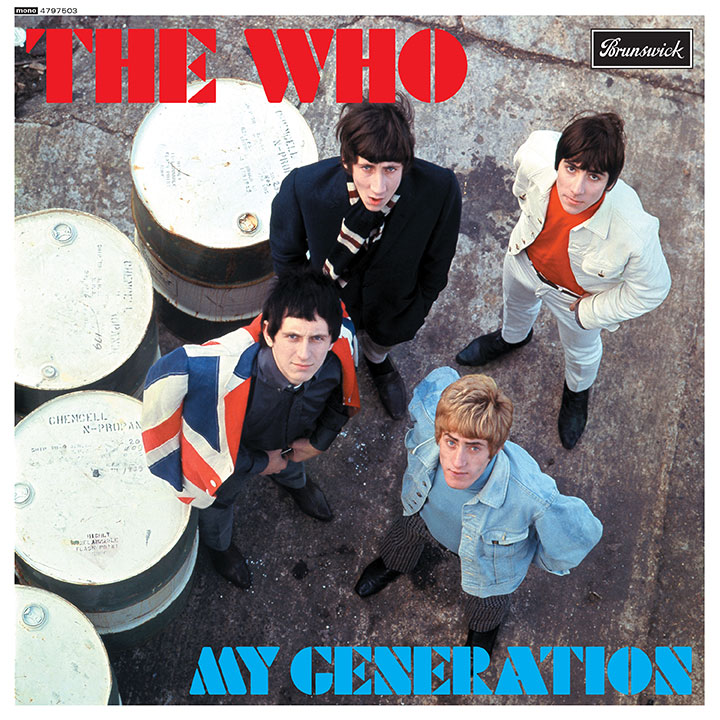

On the first day here, I had a truly memorable conversation. I had In the Court of King Crimson in my hand and was trying to cover different parts of the contorted face with my hand in order to understand the artwork, when my eyes met those of an economics professor who was beaming that a young chap was perusing a Sixties’ album. As soon as I saw him, he exclaimed ‘My generation!’

‘No, that was The Who. This is King Crimson,’ I said.

‘The Who? What? Oh!’ He paused and laughed, then resumed: ‘No, what I meant was that this music is from my generation… I was there.’

In retrospect, I think I knew that when he said ‘my generation,’ he meant his generation and not My Generation. Perhaps I said so because I wanted to prolong this conversation.

It seems shocking that old gentlemen and ladies who were there in the Fifties and Sixties so coolly remark that they were there when this album was released or that single came on the radio. Do they realize how lucky they are?

For the next half-an-hour, we kept talking of different artists, giving each artist an airtime of not more than two minutes. He soon moved to non-English, Irish, Scottish artists.

‘Have you heard Rory Gallagher?’

‘Yes, yes! Irish Tour 1974, and… and,’ trying to remember, I coughed out ‘Photo Finish!’ I was too excited that I had met someone in perhaps six years who had heard Gallagher. ‘And do you know, he had a band called Taste, and that after the death of Brian Jones, he was auditioned by Mick Jagger for The Rolling Stones. He was accepted, of course, but declined the offer. And, Gallagher opened an Aerosmith concert, and even after Aerosmith came on stage, fans kept shouting ‘Rory! Rory!’ for forty minutes!’ Then, with the fear of offending him, I shut myself up.

But he calmly resumed, ‘Yes, he was in a band called Taste. Have you heard Bert Jansch?’

‘Of course! He performed at the Isle of Wight 1970. He was known as the Jimi Hendrix of acoustic guitar. But his fans insisted that it was Hendrix who was the Jansch of the electric guitar. Jimmy Page copied so many of his licks.’ (Led Zeppelin’s self-titled debut album has a song called ‘Black Mountain Side,’ which is most certainly a cheap imitation of Bert Jansch’s ‘Black River Side’ that appears on the Glass Onion album.’)

I told him I feel sorry that British youngsters do not listen, or even know of British Invasion bands, let alone other really good British groups, and that most of them have turned to crap, run-of-the-mill American hip-hop music. (Not that USA produces bad music. Jazz was a product of USA; and the Americas inspired European composers like Antonín Dvořák. The twentieth century would be incomplete without American composers Samuel Barber and Aaron Copland. Besides, I am sure George Harrison would not have been able to connect three notes had it not been for Chuck Berry. Paul McCartney, for sure, wanted to be like Elvis Presley.)

‘Yeah, perhaps they have moved on,’ he somehow managed to say.

‘Or, moved back?’

‘Well, I cannot say so today!’

‘Anyway, do you like Tommy and Quadrophenia?’

‘Well, to be honest, I never liked The Who much.’

‘Oh… I love The Who! What about Yes? Yes did some crazy stuff, their bass player was…’

‘Chris Squire…’

‘Do you play any instrument,’ I finally asked the question that had been going on in my mind for long.

‘I used to play the drums…’

‘Like Keith Moon?’

‘Not really, I liked John Bonham a lot.’

‘Oh…’

‘And Deep Purple.’

I almost shrieked with delight when he said Deep Purple. Where I grew up, if you were a serious listener of rock, you simply had to have two bands – Pink Floyd and Deep Purple – on your playlist. I, thus, could not fathom why so many Brits and Americans, not only from my generation, but also from my parents’ generation had never really seriously listened to Purple.

‘Oh yes, Ritchie Blackmore was amazing!’ I shouted and some people looked towards at us. I couldn’t care less.

‘Not Ritchie Blackmore. Who was the drummer…’

‘Ian Paice!’

‘Yes. Have you heard the drum intro to Fireball?’

I used to listen to the entire album of Fireball (and Who Are You) religiously during my trips from my home to college every day. So when he mentioned Fireball, it was its riff that played in my mind, but it was the drum solo was playing in his mind. ‘Do you remember the drum intro,’ he said, ‘I don’t know how he [Paice] plays that: chu-chik-ta-chik-chik,’ he tried to sing the drum line. ‘Pure genius,’ he concluded.

I had to listen to the title track again, this time paying attention to the drum line. I had always admired Paice, but usually whenever I heard Deep Purple, my ears focused on Ritchie Blackmore and Roger Glover’s bass line. When my ears got a break, I focused on Jon Lord’s keyboards. I wonder why he didn’t mention ‘The Mule’s drum line, from the same album.

‘Not just the drum solo, Fireball in itself is a really underrated album. It has gems: ‘Anyone’s Daughter,’ ‘Demon’s Eye’. Have you heard Deep Purple’s first three albums, they’re my favourite?’

‘I don’t remember that, really. But I really remember In Rock.’

‘Oh, that. ‘Child in Time,’ ‘Speed King,’ ‘Black Night’. And then they had Fireball, and then they had Machine Head, and then they came out with Who do We Think We Are?, and then Ritchie Blackmore left the band.’

For the next twenty minutes, we kept exchanging notes on artists, kept quizzing each other. Eventually, he said ‘you know more Sixties’ bands than I do.’

‘I think that’s only right,’ I responded, ‘because there is a saying: ‘If you remember what happened in the Sixties…’

‘…Then you weren’t really there. Yeah?’

I could see he was in a real hurry now. Although I could have spoken to him all day long, it seemed unfair to hold him up any longer. But not before promising him that I will make a catalogue of all British groups, that have since slipped off public minds – this time, for my generation.

The promise still stands, and I hope to fulfil it next week.